Ortaköy Mosque looking towards the Bosphorus Bridge, which links Europe and Asia.

Istanbul, a city of 14 million people in northwestern Turkey, is the world’s only city that straddles two continents. The 17-mile long Bosphorus strait (shown below), which bisects today’s vast metropolis, forms the dividing line between Europe (Thrace on the left bank) and Asia (Anatolia on the right bank). The Bosphorus links the Black Sea (top) and the Sea of Marmara (bottom), which empties into the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas far to the southwest.

A bridge completed in 1973 (photo at top of post) spans the Bosphorus at the very center of Istanbul, making it possible to drive from Europe to Asia in a distance of slightly less than a mile. While Ankara is the capital of the modern Republic of Turkey, Istanbul is the de facto capital of Turkish culture, finance, art, commerce and gastronomy. With a population three times that of Ankara, Istanbul is by far the largest city in Turkey, and the vast majority of its citizens are Turkish-speaking Muslims.

Located less than 130 miles from the borders of both Greece and Bulgaria to the west, Istanbul, known in ancient times as Byzantium, was a Greek-speaking city that rose to prominence under Roman Emperor Constantine, who had liberated the Christian faith from centuries of Roman persecution. Constantine the Great, the first Roman Emperor to convert to Christianity, proposed that a new Eastern capital should represent the integration of the East into the Roman Empire as a whole, and he declared Byzantium the capital of the Eastern Empire in the year 330. Byzantium was renamed Constantinople in his honor. Two hundred years after Constantine’s declaration, Emperor Justinian, the greatest of the early rulers of Byzantium, enlarged the empire until it reached from the Black Sea to Spain.

Map below: Modern Turkey's borders with Greece, Bulgaria, Georgia, Armenia, Iran, Iraq and Syria; Istanbul is located at the upper left of the green area:

Istanbul is one of the oldest still-inhabited spots on earth. For millennia it was thought that the area was first settled by Greeks in 667 BC. However, a recent excavation for a just-opened subway line that travels under the Bosphorus Strait revealed that Istanbul was settled 8,000 years ago. The body of water known as the Golden Horn divides the northern and southern parts of the Old City. The partially-walled Sultanahmet area is the oldest section of the city, a peninsula bordered by the Sea of Marmara to the south and the Golden Horn to the north.

In the early 20th century the city’s name was again changed, this time to Istanbul, when the capital was moved to Ankara. Today Istanbul is the world’s fifth largest city, and it is ranked as the largest city in Europe. It should be noted that since the 1920s Turkey has been a secular country, and even though most inhabitants are Muslim, Shar’ia law does not apply; for example, the city is full of bars and restaurants serving alcohol. Don’t miss bargain priced local Efes beer and Turkish wines (especially the reds).

As of Sept. 2015, 1 U.S. dollar = 3 Turkish lira; one Turkish lira = U.S. 33 cents.

Uyan Hotel **** (Sultanahmet); if you take a taxi to return to the hotel, be sure to hand the driver a hotel business card. It's tricky to find and on a pedestrian street. If all else fails, tell your driver to drop you off at the Four Seasons Hotel in Sultanahmet (there is another Four Seasons Hotel on the Bosphorus, so be sure to say Sultanahmet).

Address: Utangaç Sokak No 25*

For the brave - want to try to say the above address to your taxi driver? Good luck!

*Utangaç (oo-tahn-GAHTCH) Sokak (SOH-kahk) 25 = yirmi beş (YEER-mee BESH)

By the way, the street name, Utangac, means "bashful." Odd, I know.

The hotel was built around 1930 as a private home. It was converted into a hotel in 1992, and its 24 rooms are spread over four floors beneath a rooftop terrace with spectacular views of historic monuments and the Marmara Sea. Breakfast room, computer stations and bar all on the fourth floor. An iron stairway leads up to the roof terrace.

Sightseeing:

The following tourist attractions all lie within walking distance of the Hotel Uyan, and many of them can be viewed from the hotel’s roof terrace. Note: if you are a light sleeper, bring ear plugs to protect against the ear-splitting morning call to prayer at 5:44 a.m. (!) and again at 7:13a, 12:51p, 3:57p, 6:26p and 7:52p; all times for mid-October). Mosques are closed to tourists (and non-Muslims) for about 30 minutes following these times.

■ Sultanahmet Square, the centerpiece of the Old City, links the major sites of Hagia Sophia (above) to the north and the Blue Mosque on its southern edge. The square houses a large round fountain surrounded by a grassy expanse. Hucksters sell maps and scarves (for women, whose heads must be covered when entering a mosque), and they can be “persuasive”. The scarves are cheap and make great souvenirs.

■ Ayasofya Hürrem Sultan Hamamı (Turkish bath house, above). Located in a corner of Sultanahmet Square opposite Hagia Sophia, this luxurious stone bath house was designed and built in 1556 by chief Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan for Roxelana, a kidnapped Polish slave who resided in the Topkapı harem from age 14 and eventually became a wife of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

The sections for men and women are mirror images of each other, and treatments range in price from U.S. $95-$190. Restaurant on premises. Completely restored in 2008, the facility boasts fine lattice staircases, fountains and marble floors (above). Open 8a-10p; consistently rated the best in the city.

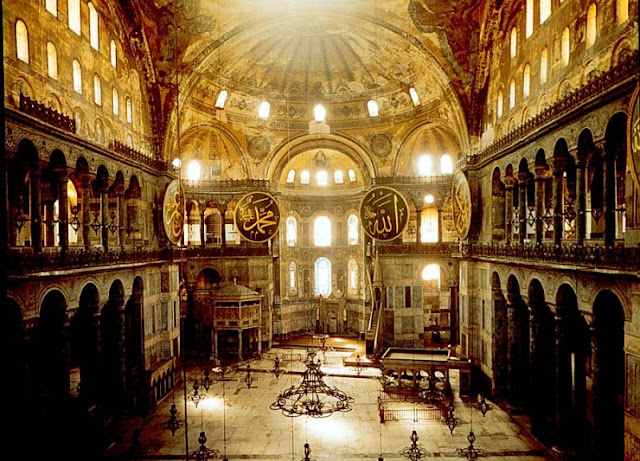

■ Hagia Sophia (Aya Sofya in Turkish). CLOSED MONDAYS. Open 9-5. Adjacent to the northern perimeter of the fountain park known as Sultanahmet Square. The name means “Holy Wisdom” in Greek, not Saint Sophia, even though maps often label it “St. Sofia.” Dating from the sixth century (making it nearly 1,500 years old), this great Byzantine building was originally a Christian basilica constructed in 537 for Roman Emperor Justinian I. The first two Christian churches on this site (built in 360 and 415) had been destroyed by rioters. A masterwork of engineering, the huge 100-ft. diameter dome covers what was for over 1000 years the largest enclosed space in the world (photo below). The church was looted by the fourth Crusaders in 1204 and became a mosque in 1453, when the Ottomans conquered the city (detailed history at end of this post). They added the stairs of a minbar (pulpit), minarets and fountains at that time. In 1935 Atatűrk, who secularized the entire country, converted it into a museum, settling the dispute between Christians and Muslims, who both claimed it. As a museum, it is illegal to pray on the premises, a policy that is strictly enforced. Don't miss the excellent Christian mosaics, which had been painted over by the Ottomans, especially those in the upper gallery, reached by a stone ramp to the left of the entrance. Note the gilt and stone mihrab (elaborate concave niche indicating the direction of Mecca, slightly to the right of center, which had faced Jerusalem when it was a Christian church), and huge discs of Arabic calligraphy at the base of the dome (the one on the left in the far distance above the chancel says Muhammed, the one on the right Allah, and the rest of them are names of Muhammed’s family members).

As of 2015, admission is 30 Turkish Lira (TL), payable by credit card or Turkish currency. A fine gift shop is located near the exit. There may still be some scaffolding inside, as the 2013 reconstruction has not yet been completed.

■ Topkapı Palace ((Topkapı Sarayı in Turkish). CLOSED TUESDAYS. Open 9-5. Note the undotted “i” at the end, pronounced “uh,” thus TOHP-KAH-PUH. This palace (1465) complex spread over 200+ acres is a cluster of buildings that served as the imperial enclave of the Ottoman emperors until the Ottoman Empire was dissolved in 1923. The campus structures, added to over centuries, are lavishly decorated and spread among four courts of increasing grandeur. Main entrance gate shown above. In the second court is the entrance to the 400-room Harem (separate admission, may be visited only by joining a guided tour), home to the Sultan’s mother, wives, children, concubines, eunuchs and their servants. Harem entrance shown below:

The third court has the Imperial Treasury, not to be missed. The complex houses both Islamic and Christian relics, rugs, porcelain, etc. The views from the Fourth Court over the Bosphorus are spectacular. On display are the cloak and sword of the Prophet Mohammed. The stand-alone library building’s interior (1719) is remarkably serene, its walls adorned with tiles and stained glass windows. The Circumcision Pavilion (1640) was used for circumcision rituals of the Ottoman princes. The kitchens, with their tall smokestacks, employed a staff of 500 who prepared 4,000-6,000 meals per day. Admission 30 TL (credit cards and Turkish currency accepted. Harem 15 TL extra). Note: As of April 2015, some of the areas of the palace were closed for restoration.

■ Blue Mosque / a.k.a. Sultanahmet Mosque (Sultanahmet Camii, in Turkish; the “C” is pronounced like the “j” in pajamas). Open 9-9 daily. With its six minarets and monumental architecture the Sultan Ahmet or 'Blue' Mosque (1616) impresses from the outside (photo above, with the Sea of Marmara in the background). The blue ceramic tiles inside give the building its tourist name (below).

Major portions along the mosque’s south perimeter are built on the old foundations of the Imperial Byzantine Palace that faced the Hippodrome. Unlike Haghia Sophia, this is still a working mosque. IMPORTANT: entry is through the courtyard on the SW side, which is the back side of mosque. No bare shoulders (shawls are provided) and everyone will need to remove their footwear (bags are provided that you can place your shoes in and carry along with you). No admission charge, but donations are welcome upon exit. The mosque is closed during prayer times, but mosque volunteers provide you with a free presentation about the Mosque and Islam during those times in the Mosque's conference hall, the building with the "Free Event" sign that will be on your left if you are approaching the Mosque from Sultanahmet Square.

When visiting any mosque, women need to wear head scarves (can be bought nearby or borrowed on site for free). Everyone needs to cover their legs (no shorts or short skirts). It is considered rude and sacrilegious to photograph the men while they engage in ritual foot washing before entering the mosque’s interior. You were likely awakened this morning by the calls to prayer blasted over the neighborhood through speakers located in the minarets -- five times a day.

■ Arasta Bazaar is a single lane 17th century open-air pedestrian shopping thoroughfare (above), one of the best in the city. Quality is high, prices are reasonable. It hugs the rear of the Blue Mosque, and entry is from the street on which the Hotel Uyan is located, a couple of blocks out the front door to the right and down the hill. It is opposite the Blue House Hotel (aptly named) just behind an open air restaurant/café. Turn right at the Mozaic Museum sign, and you’re right in the middle of it. Clothing, jewelry, textiles, art, carpets, crafts, watches. Kilim pillow covers make great souvenirs, and they fold flat for tucking into your luggage. Best of all, shopkeepers will not bother you if you window shop – i.e., they will not run outside to accost you with a sales spiel. That alone makes it a pleasant and unique experience. When the bazaar was built, the rents from its vendors helped pay for the upkeep of the great Blue Mosque looming above it.

■ Basilica Cistern (Yerebatan Sarnici in Turkish). 9-6:30 daily. Carefully cross the street with the tram tracks where the line for Hagia Sophia forms; turn right for a few yards while taking note of the Million marker on your left, a partially intact marble pillar dating back to the 4th century AD. It was the starting point of any distance measured within the empire during the Byzantine era. Then take the first street to the left, where the entry to the cistern is on the left. This is a massive underground cistern (photo above) built by Roman Emperor Justinian in 532 to provide water to the city in cases of siege (there were many). A walkway winds between the stone pillars, and lights and piped music add to the eerie atmosphere. Throw a coin into the carp-filled pools to make a wish. The statue of Medussa at the far end is impressive. The water level used to be just below the capitals at the top of the columns. 20 TL cash only, no credit cards. Souvenir shop at the exit. Coffee shop and snacks on main level.

■ Hippodrome (built 203), located right in front of the Blue Mosque. This was the center of ancient Byzantine and Roman Constantinople, where sporting (chariot and horse races) and massed social events took place. The original oval building (illustration above) of terraced viewing stands no longer exists, but several obelisks and sculptures that run down the center of the arena (spina) remain: the 3,500 year old Egyptian obelisk (relocated from Luxor; note how much street level has risen since the third century, since the bases of these monuments sit far below today’s pavement); the rather ragged-looking stone obelisk at the other end (from the 10th century, it was originally covered in gilded bronze plaques that were looted by members of the fourth crusade) is shown below; and the so-called spiral “Serpent Column” that sits between them was brought from Delphi by Emperor Constantine (a golden bowl supported by three serpent’s heads used to sit atop it; it was also pillaged by the crusaders). The illustration above shows the city's main harbor on the Sea of Marmara in the foreground and the Hippodrome's adjacent Great Byzantine Palace complex to its right.

The four bronze horses that stand today in the facade of St. Mark’s basilica in Venice used to be on top of the Emperor's box overlooking the Hippodrome, but they were also looted by the crusaders in 1204. The hippodrome abutted the Great Byzantine Palace, which covered all the area under today’s Blue Mosque all the way to Hagia Sophia. Thus the Hotel Uyan sits atop remains of this ancient palace.

The so-called German Fountain (Alman Çeşmes, in Turkish) at the end of the hippodrome’s northern edge is a neo-Byzantine style fountain structure sent as a gift by German Kaiser Wilhelm II to the Ottoman Sultan in 1898. Restoration was completed in 2014.

■ Grand Bazaar (Kapali Çarşı in Turkish) is the oldest (1461) and largest covered market in the world, with 61 lanes lined with more than 3,000 shops that cater to approximately 300,000 bewildered tourists every day. 30,000 people work there. A rooftop view of a mere portion of the Grand Bazaar is shown above. Public restrooms inside (take some coins with you), as well as several cafés. Shops offering similar wares are grouped together (jewelry, leather, carpets, antiques, etc.). Hours 9-7, closed Sundays. Haggling over the price is the norm when shopping -- merchants will look at you in disgust if you accept their first quoted price. Shopkeepers let you offer a price lower than the retail price; the best bet is to start from about sixty percent of whatever is being asked by the shopkeepers. They will usually settle at 75 percent of their original demand, after some pleasant bargaining. Once a price agreeable to both is met, the sale can be finalized.

The bazaar is a pleasant 15 minute walk up Divan Yolu street from Hagia Sophia. Cross the tram tracks in front of the square facing Hagia Sophia (where the line forms) and just follow the tram tracks slightly uphill along Divan Yolu (Road to the Imperial Council; its course has not changed since the fourth century). Make no turns and stay on the right-hand side of the street; after about 5 minutes visit the elevated cemetery. Turkish-style gravestones have a skinny shape; you may remove your shoes to enter the adjacent mosque on the corner of the property. Note the shape of the caskets inside – we are accustomed to flat top caskets.

Farther up the street are the remains of the Column of Constantine (Burnt Column) dedicated in 330 to commemorate the declaration of Byzantium as the new capital of the Roman Empire. A statue of Emperor Constantine the Great as Apollo used to sit atop it. The column was the centerpiece of the city’s oval shaped plaza lined with colonnades to create a Roman-style forum. A short distance farther (again, on the right), one comes upon the Grand Bazaar. Look for signs with an arrow: Kapali Çarşı – Grand Bazaar. Pick any one of the 21 entrance gates. Maps available once inside.

Be sure to visit a few of the hans surrounding the Grand Bazaar buildings, where craftsmen continue the ancient traditions of producing handmade wares. Istanbul was on the fabled Silk Road* trade route, and merchants brought their goods to "hans", often adjacent to mosques. A han (caravansary) functioned as an inn, provided restful accommodations for both the traveling merchants and their camels/horses while they carried out their business of selling their wares. Most hans had courtyards with a fountain for washing, a kitchen and a tea house.

*The Byzantine Empire had a monopoly on silk production in medieval Europe.

Restaurants, Cafes and bars:

Palatium

Go left out the front door of the hotel, then turn right at the corner (the Four Seasons hotel will be on your left). At the end of the block you'll be staring into the huge windows of Palatium, a popular spot for drinks, snacks, breakfast, lunch and dinner. Open until very late, service is straight through from opening until closing; the entire wait staff speaks flawless English. Menu in English; indoor and outdoor seating. You will likely visit Palatium more than once during your time in Istanbul.

A portion of the floor is glass (photo at right), so that guests may peer down into the excavated ruins of the Grand Byzantine Palace. A stairway from the rear courtyard allows direct access down to the site. Make sure you see it.

Palatium is also a great place for smoking a Turkish water pipe (nargile in Turkish; also called a hookah). The centuries-old practice has seen a renaissance since the 1990s, and it is not associated with any drug or youth culture. It's a great way to slow down and relax.

The staff will instruct you on its use and will help you choose the tobacco flavor. Apple is the most popular, but my favorite is cappuccino (odd, I know). Your waiter will supply hot coals, bring mouthpieces for everyone, and do everything except smoke for you. Note: never lift the glass vessel off the floor, and don't pass the hose to others (just put it down next to the glass bowl). Smoke lightly - do not take deep draughts.

This is communal activity, not something to try alone; plan on an hour or two, avoiding loud conversation. The nargile became popular during the 1700s in Istanbul, at the height of the Ottoman Empire. To smoke with the Sultan was the ultimate honor. For an authentic experience, sit on one of Palatium's "bean bag" style kilim-covered chairs up near the window. I still dream about this place.

Albura Kathisma Restaurant

The name means "Imperial Box," a reference to the emperor's box at the hippodrome, his perch for viewing athletic competitions and chariot races. You can tell that this is one of the better restaurants in Sultanahmet, because no one will come out to set upon you, beseeching you to come inside. They don't need to.

At least one person at your table should order something baked in a clay pot, which is broken open with great flourish at tableside.

How to get there: turn left upon exiting the hotel, then right at the corner. At the dead end, turn left after crossing the street in front of Palatium. Take the next possible right. At the next corner you'll see the Hotel Empress Zoe on the left. Turn right down a very long street of back-packer type establishments. Albura Kathisma will be on your right. Indoor/outdoor seating. Ask to be led to the stairway to the underground excavations of the Great Byzantine Palace, which adjoins those at Palatium.

Rumeli Cafe and Mozaik

These two restaurants share a kitchen, and both have indoor and sidewalk seating. Rumeli (right) is housed in an old printing factory and serves Ottoman cuisine (much more delicious than you'd think).

Mozaik (at left), right next door, occupies a restored grand Ottoman private home. Both have a warren of small, atmospheric rooms, some with fireplaces. There are no views to speak of, so it's best to sit inside and enjoy the cozy atmosphere. Both restaurants have provided some of the finest meals I've ever eaten in Istanbul.

How to get there: Find your way to the square in front of Hagia Sophia, where the line forms. Cross the street with the tram tracks and walk left up the gentle incline, keeping on the right side of the street. Just before the Sultanahmet tram stop, a pedestrian only lane veers off to the right. Enter the lane to find adjacent restaurants Mozaik and Rumeli, both just a few yards up on your right.

Hafiz Mustafa 1864

Need something to satisfy your sweet tooth? Amazing puddings, cakes and baklava (center photo; baklava was invented in the kitchens of Topkapi Palace, a short distance away). Picture menu. No alcohol (just tea, coffee, fruit drinks). Open from breakfast until very late at night.

Location: Divanyolu Cad. #14. With Hagia Sophia at your back, cross the street with the tram tracks and walk uphill, staying on the right side of the street. Just before the Sultanahmet tram station, Hafiz Mustafa 1864 is on your right. Entrance is recessed a few steps down from sidewalk level (easy to miss).

Return visit: The Galata District

The steep Galata district lies north of the Golden Horn waterway, directly opposite the Sultanahmet peninsula. Galata is Greek for "stairway," and the streets are often so steep that the sidewalks are indeed stair steps.

Even after the Muslim Ottomans captured the city, this district remained Latin and Catholic. Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror later made this a residential area for Greeks and Jews, so even then it remained non-Muslim. In the nineteenth century foreign embassies sprang up here, and eventually every national group (French, German, English, etc.) had a separate enclave with its own houses of worship and schools. Wealthy Muslim families from other neighborhoods usually sent their children to these schools.

The 200 ft. tall stone Galata Tower was once part of the walls that protected this neighborhood. Built by the Genoese in the 14th century, the tower was used as a lighthouse and to monitor maritime traffic along the Golden Horn and Bosphorus. It later saw use as a fire lookout tower. It may be visited by elevator, but the line is often quite long and the view just so-so. Admission: TL 19

Hotel Adahan Istanbul

Return to Istanbul, one overnight at:

Hotel Adahan****

Galata District north of the Golden Horn

General Yazgan Sokak #14

Istanbul

Known for its rooftop restaurant (left) and hotel interiors restored and furnished in a somewhat spare style.

Origin of street name: General Yazgan (1876-1961) was a senior commander involved in the Turkish War of Independence (1919-1923). He had also distinguished himself in the 1897 Ottoman-Greek War, the Tripoli War, the Balkan Wars and WW I. He retired in 1931 and died in Istanbul in 1961.

The Adahan hotel building used to be the 19th century in-town mansion of the Camondos, a famous Jewish family with a tragic destiny. Count Moïse de Camondo was born in Istanbul in 1860 into a Sepharadic Jewish family that owned one of the largest banks in the Ottoman Empire. When World War I broke out, Moïse’s son Nissim was killed in an air battle. After this tragic loss, the Count decided to bequeath his private residence in Paris to “Les Arts Décoratifs” in memory of his son, and the Musee Nissam de Camondo opened in Paris on the edge of the Parc Monceau in 1935, the year after Moïse de Camondo died. During World War II, further tragedy ensued, when his daughter Béatrice, his son-of-law Léon Reinach and their children died in the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz. Thus the Camondo family line died out. The Paris museum is housed in a mansion built by Count Moïse de Camondo to resemble the Petit Trianon. It is still open today as a museum maintained as if it were a private residence preserved in its original condition, with all of the Count's collection of 18th century French furniture and art objects intact.

The Hotel Adahan is on the same sloping street as a landmark modern restaurant/café called The House Café, located just a longish block away at the corner of Tünel, which leads to an underground funicular built to navigate the steep hill down to the Golden Horn waterway. Exit the hotel front door and turn left. The House Cafe (est. 2005) is on a corner on your right. This restaurant (below) was the first of nine spectacularly successful eateries, all named The House Cafe, throughout the city and beyond. Stop here for just a cup of coffee or tea, or a full meal. Restrooms in the basement. Indoor and outdoor seating. Kitchen open 9:00a - 11:30p; drinks/snacks served until 1:00a daily.

From The House Café you’re just a block shy of Istiklal Cadessi (Independence Avenue, formerly called the Grand Rue), the fabled pedestrian boulevard that leads all the way up to Taksim Square. This street is chock-a-block with pedestrians out for a stroll, a drink, street food, a full meal or a shopping expedition. It is especially alluring after dark, when all the signs are illuminated. An historic tram line (left) runs the length of it, but the old wooden cars are impossibly crowded, and there are usually long lines of people waiting to board. Listen for the tram’s bell and get out of its way immediately. You’ll see what I mean. Istiklal Ca. is resplendent with grand movie theaters, bookstores, galleries and even modern shopping centers. This area was occupied by Italians – the Genoese and Venetians – during Byzantine times. Many of the former grand embassy buildings, now chanceries, may still be admired.

Pera Palace Hotel

A modern day visitor cam walk among the hallways and public spaces of this grand historic nineteenth-century hotel where state leaders and world famous personalities once stayed, including Greta Garbo (rm. 103), Mata Hari (rm. 104), Yehudi Menuhin, Tito of Yugoslavia, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (rm. 308), Rita Hayworth, King Carol of Romania, Ian Fleming, Mae West, President of France Valery Giscard d‘Estaing, Margot Fonteyn, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Ernest Hemingway (rm. 218), Kaiser Wilhelm II, Graham Greene, Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Josef, Alfred Hitchcock, King Ferdinand of Bulgaria, Matt Dillon, Leon Trotsky (rm. 204), Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson, Italian King Victor Emmanuel III, Sarah Bernhardt (rm. 304), the Shah of Iran Reza Pahlevi (rm. 202), Josephine Baker, King George V, John dos Passos, and many more, such as Joseph Goebbels (generally omitted from hotel promotional literature).

Directions: Turn right out the door from the hotel, then turn right at the corner onto Meşrutiyet Cd. (Constitution Street; a big improvement in street name, since before the establishment of the modern Turkish Republic, this street was called "graveyard" street) for a pleasant stroll up to the venerable Pera Palace Hotel, which will be on your left). Opened in 1892, it was built by the International Wagons-Lits company for the purpose of housing passengers of the just opened Orient Express luxury train line from Paris to Constantinople, as Istanbul was then called. Passengers would arrive at the Sirkeci train station on the opposite shore of the Golden Horn and be transported across the water and up the hill to the hotel via sedan chairs. One of the originals (at right) is displayed in the hotel lobby, just to the left of the reception station. The regular Orient Express line ceased operations in 1977, but a cluster of restored train cars now makes an annual pilgrimage to Istanbul and the hotel.

The Pera Palace was the city's see-and-be-seen hotel choice, and anybody who was anybody stayed there. Detective writer Agatha Christie allegedly wrote her 1934 novel Murder on the Orient Express while staying at the hotel, and the main restaurant of the hotel (down on the spa level) is named Agatha in her honor. Poke around the main floor rooms until you spy the original wrought-iron cage elevator (below). Stop by the Orient Bar (up a few steps and behind reception) for an expensive cocktail and a chance to perch in a chair upholstered in royal purple velvet. Listen for the echoes of Ernest Hemingway and Graham Greene. For those who prefer pink damask, visit the hotel's Patisserie for confections and hot tea. A grand afternoon tea is served in the Kubbeli Saloon (photo at end of post), a reception hall off the bar (the room with the large Schiedmayer grand piano and a two-story adjacent space with massive chandeliers and six domes in the ceiling). A $32 million restoration was completed in 2010.

The “museum hotel” moniker is demonstrated by the Agatha Christie Museum, room 411, now preserved in her honor. She was a frequent visitor during the 1920s and -30s. Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the modern Turkish Republic, is memorialized by many personal artifacts housed in room 101, where he first stayed in 1917. That room is painted sunset pink, his favorite color. No kidding.

On the morning of March 11, 1941, the hotel endured its most devastating moment when a tremendous explosion shook the hotel lobby, from a bomb planted in a suitcase by pro-Nazi saboteurs. The bomb, intended to detonate during the British Legation’s train journey from Sofia, Bulgaria, instead exploded as the legation was checking into the hotel. Six people died, and dozens were injured. The suitcase had been planted unnoticed among the legation’s luggage as the train was about to depart from Sofia. A short time after the tragedy, another unidentified suitcase, determined also to contain explosives, was hurled from a hotel window without detonating.

From that point the hotel, along with its neighborhood, entered a sort of genteel decline, until it closed its doors in 2008 for a top-to-bottom restoration. The fabled Pera Palace Hotel reopened on September 1, 2010. The international luxury Jumeirah Group (Dubai, United Arab Emirates), today manages the hotel, now owned by Beşiktaş Marine and Tourism Investments Industry Inc., a shipping company.

A photo of the domed ceiling of the Kubbeli Saloon.

For further study:

Istanbul History from 360 to the Present Day

During his 38-year reign, from 527 to 565, Emperor Justinian erected hundreds of churches, libraries and public buildings throughout his vast empire. Hagia Sophia – written Aya Sofya in Turkish (the name translates from the Greek as "Sacred Wisdom") – was his crowning architectural achievement, and its history parallels that of the Turkish nation itself. The first church structure on the site, dedicated in 360, was destroyed during riots in 404; the second church, dedicated in 415, burned down during the Nika revolt of 532, which caused vast destruction and death throughout the city. Immediately after the riots, Emperor Justinian ordered the church rebuilt, and the building we see today was dedicated on December 27 in the year 537 – exactly 1,478 years ago. Unfortunately, the first dome collapsed after just twenty-one years, but Justinian had it rebuilt in 562 to an even greater height. Constructing the most important building in the Eastern Christian world was no easy task, as it was to contain a collection of relics and architectural splendors heretofore unknown.

Constantinople was by far the largest and wealthiest European city of the Middle Ages, and for more than 900 years Hagia Sophia was the seat of the Orthodox patriarch (a counterpart to the Roman Catholic pope) as well as the central church of the Byzantine emperors, who lived in a palace next door on property now the site of Sultanahmet Square, the Blue Mosque and Marmara university. Hagia Sophia was the summation of all that was the Orthodox religion. Pilgrims came from across the Eastern Christian world to view its icons and sacred relics: pieces of the True Cross, the lance that pierced Christ's side, the ram's horns with which Joshua blew down the walls of Jericho, the olive branch carried by the dove to Noah's ark after the Flood, Christ's tunic, the crown of thorns and a vial of Christ's own blood.

This painting depicts Hagia Sophia before some of the clumsier looking buttresses and supports were added to the exterior, attached for structural support and prevention of future earthquake damage. For comparison, see aerial present-day view in last photo in this post.

For nearly a millennium no building incorporated as large a floor space under one roof. Four acres of golden glass cubes – millions of them – studded the interior to form a glittering canopy that reflected flickering candles and oil lamps. Forty thousand pounds of silver embellished the sanctuary. Columns, many of them recycled from other ancient buildings, were crowned by new capitals so intricately and deeply carved that they seemed as fragile as lace. Blocks of marble, imported from as far away as Egypt and Italy, were cut into decorative panels that covered the walls. The astonishing dome, measuring 100 feet from east to west, soared 180 feet above the marble floors.

In the 11th century, the Byzantines suffered the first in a series of devastating defeats at the hands of Turkish armies, who surged westward across Anatolia (Asia Minor), steadily whittling away at the empire. The realm was further weakened in 1204 when western European crusaders en route to the Holy Land captured and greedily looted Constantinople. Their pillaging of Hagia Sophia during the fourth crusade was the greatest loss of artistic and literary treasures in the history of Christianity. The city never fully recovered.

By the mid-15th century, Constantinople was hemmed in by Ottoman-controlled territories. On May 29, 1453, after a seven-week siege, the Turks launched a final assault. Bursting through the city's defenses and overwhelming its outnumbered defenders (10,000), the invaders (80,000) poured into the streets, sacking churches and palaces, murdering anyone who stood in the way. Terrified citizens flocked to Hagia Sophia, hoping that its sacred provenance would protect them. They prayed desperately for an avenging angel to swoop down before the invaders reached the great church.

Instead, the sultan's infantry units battered their way through the great wood-and-bronze doors, bloody swords in hand, bringing an end to an empire that had endured for 1,123 years. The church, which was understood to embody heaven on earth, was ravaged by aliens in turbans and robes, smashing tombs, scattering bones and hacking up icons. There was an appalling mayhem of screaming wives being ripped from the arms of their husbands and children torn from parents, to be chained up and sold into slavery. For the Byzantines, it was the end of the world. Memory of the catastrophe haunted the Greeks for centuries.

That same afternoon, Constantinople's new overlord, Sultan Mehmet II, rode triumphantly to the shattered doors of Hagia Sophia. Mehmet, one of the great figures of his age, was as ruthless as he was cultivated. The 21-year-old conqueror spoke Greek, Turkish, Persian and Arabic, as well as some Latin, and he was an admirer of European culture, even patronizing Italian artists. Mehmet was ambitious, superstitious, cruel, intelligent, paranoid and obsessed with world domination. He saw himself as coming not to destroy the Byzantine empire, but to become the new Roman emperor. He later cast medallions that proclaimed him "Imperator Mundi" – Latin for Emperor of the World.

Hagia Sophia was the physical embodiment of imperial power, and now it was his. He declared that it was to be protected and henceforth would serve as a mosque. Calling for an imam to recite the call to prayer, he strode through the handful of terrified Greeks who had not already been carted off to slavery. Mehmet then climbed onto the altar and bowed down to pray. Within a week Hagia Sophia was hosting Muslim services. Thirty ships of a Venetian fleet sailing to Constantinople’s relief saw Turkish flags flying over the city, turned around, and sailed home. There was a problem, however. The great church of Hagia Sophia was built to face Jerusalem, while all mosques faced Mecca. Since the building could not be realigned, a "mihrab" (prayer niche) was installed to indicate the direction of Mecca. Today's visitors will notice that the mihrab inside Hagia Sophia is off-center for this reason.

Among Christians elsewhere, reports that Byzantium had fallen sparked widespread anxiety that Europe would be overrun by a wave of militant Islam. People wept in the streets of Rome, and there was mass panic. With the conquest of Constantinople, The Ottoman Turks had strategically blocked all land routes to Europe, and Europeans had to find other ways to trade with Eastern countries. The once great city of Constantinople was virtually depopulated - as many as 50,000 sold into slavery - and the world as they knew it had come to an end.

However, the Turks treated Hagia Sophia with respect, and the city quickly recovered. In contrast to other churches that had been converted into mosques, the conquerors refrained from changing its name, merely adapting it to the Turkish spelling: Aya Sofya. Sultan Mehmet recognized Hagia Sophia's greatness and saved it. Remarkably, the sultan allowed several of the finest Christian mosaics to remain, including images of Christ (shown), the Virgin Mary and images of the seraphs, which he considered to be guardian spirits of the city.

During this period, minarets were built around the perimeter of the building and exterior buttresses were added for structural support. Under subsequent regimes, however, more orthodox sultans would be less tolerant. Eventually, all of the figurative mosaics were plastered over, since Islam does not allow figurative images in mosques. Where Christ's visage had once gazed out from the dome, Koranic verses in Arabic now proclaimed: "In the name of God the merciful and pitiful, God is the light of heaven and earth."

The Ottoman sultans embellished Constantinople with many mosques, palaces, monuments, fountains, baths, aqueducts and other public buildings that served the Ottoman Empire until its dissolution in 1921, following World War I. Until 1934, Muslim calls to prayer had for centuries resounded from Hagia Sophia's four minarets five times a day, from sunrise to sunset. In that year, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, modern Turkey's first president, secularized Hagia Sophia as part of his revolutionary campaign to westernize Turkey. Its status was thus reduced to a museum, which it has been ever since.

An agnostic, Atatürk ordered Islamic religious schools closed, banned the fez and veil and gave women the right to vote, making Turkey the first Muslim country to do so. He cracked down harshly on once-powerful religious orders. The sultanate was abolished in 1922, and religion was separated from the state in 1923, the year the city's name was changed from Constantinople to Istanbul. The Arabic alphabet was replaced with a Roman one. Western dress was encouraged, and all Turks were obliged to choose a surname. The branches of government were moved to the more centrally located city of Ankara, which became the secular republic's capital in 1923. The changes were so dramatic that many Turks felt their world had been turned upside down. "Fellow countrymen," he declared, "you must realize that the Turkish Republic cannot be the country of sheikhs or dervishes. If we want to be men, we must carry out the dictates of civilization. We draw our strength from civilization, scholarship and science and are guided by them. We do not accept anything else." Of Hagia Sophia he declared: "This should be a monument for all civilization." It thus became the world's first mosque to be turned into a museum. Under Turkish laws dating from the 1930s, prayer is prohibited inside Hagia Sophia.

Nevertheless, many Christians wish to have the great building returned to use as an Orthodox church, while Turkish Islamists desire the reconsecration of Hagia Sophia as a mosque. To more ideological Islamists, Hagia Sophia proclaims Islam's promise of ultimate triumph over Christianity. In November of 2006, a visit by Pope Benedict XVI to Hagia Sophia prompted an outpouring of sectarian rage. Tens of thousands of protesters, who believed that he was arriving to stake a Christian claim to Hagia Sophia, jammed surrounding streets and squares in the days before his arrival, beating drums and chanting "Constantinople is forever Islamic" and "Let the chains break and Ayasofya open." Hundreds of women wearing head coverings brandished a petition that they claimed contained one million signatures demanding the re-conversion of Hagia Sophia back into a working mosque. Thirty-nine male protesters were arrested by police for staging prayers inside the museum. When the pope finally arrived, traveling along streets lined with police and riding in an armored car rather than his open Pope-mobile, he refrained from even making the sign of the cross. In the museum's guest book, he inscribed only the phrase, "God should illuminate us and help us find the path of love and peace."

For secular Turks the possibility of Islamic radicals taking over the building brings dismay, and they believe that turning Aya Sofya back into a mosque is out of the question. They consider it a symbol of their secular republic – that it is not just a mosque, but part of the world's heritage. Whatever its ultimate fate, Hagia Sophia remains the premier monument of Byzantine civilization.

Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938) was a great military leader, a

social reformer, a persuasive and brilliant diplomat, a shrewd economist

and the first president of the modern Turkish Republic. He was

reelected fifteen years in a row, and the only reason he was not

reelected for a sixteenth time was that he had drunk himself to death by

the age of fifty-seven.

"A man born out of due season, an anachronism, a throwback to the Tartars of the steppes, a fierce elemental force of a man. With his military genius and ruthless determination, in a different age he might well have been a Genghis Khan, conquering empires."

Never in doubt of his abilities, the man excelled at every task he took on. Time and again he developed battle plans that succeeded against impossible odds. His triumph at Gallipoli against the British and Australians was nothing short of a miracle. As well, his powers of persuasion were legendary. I quote a speech he made to foreigners whose family members or loved ones had lost their lives and lay buried on Turkish soil:

"Those heroes (who) shed their blood and lost their lives... you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us – where they lie side by side here in this country of ours... You, the mothers who sent (your) sons from far away countries, wipe away your tears. Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well."

Amazing, no? The Turkish War of Independence, which ended in 1922, was the last time Atatürk used his military might in dealing with other countries. Ensuing foreign issues were resolved by peaceful methods during his presidency.

During his days as a Military Attaché in Sofia, Bulgaria (1914-1915), he adopted western European dress for the first time, usually wearing a business suit with a vest, since he had been ridiculed for his fez and Turkish military attire. He was astonished that neighboring Sofia, so near to Turkey’s doorstep, boasted an opera house, theatre, national library and a ballet company. He determined then and there that Turkey’s future must be forged upon Western European models, and that it must shed its backward, Islamic traditions. A staunch agnostic, Macedonian-born Atatürk turned the Islamic Turkish nation upside down. After seizing control of the country he abolished centuries of Shari’ah (Islamic) law, eliminated the Caliphate, implemented the Western European calendar, sent the Sultan into permanent exile and ordered Islamic religious schools closed. He cracked down harshly on once-powerful religious orders, such as the dervishes.

But he was just getting warmed up. He opposed the Turkish government's decision to surrender to the Allies after WW I, so he organized an army of resistance, which successfully defeated the Allied occupation forces. Atatürk changed the name of Constantinople to Istanbul and established a Republic with a new capital in Ankara, a more centrally located city. Atatürk became the Republic's first president. He once more set his sights on reform by banning the veil and fez, leading by example; he strutted around in Panama hats and western business suits before a shocked public. He gave women the right to vote, thus making Turkey the first Muslim country to do so. He ordered men to appear in public with their wives – even to dance with them; prior to this decree most Turkish men had never before met each other's wives. In his spare time Kemal banned polygamy. Oh, I nearly forgot – he forced everyone to take a surname. His own surname, Atatürk (meaning "Father of the Turks"), was granted to him, and forbidden to any other person, in 1934 by the Turkish parliament. He abolished the use of Arabic script and replaced it with a Latin (West European) alphabet, at the same time making secular public education compulsory, even for women, thus thumbing his nose at centuries of Islamic segregation of the sexes.

"Fellow countrymen," he declared, "you must realize that the Turkish Republic cannot be a country of sheikhs or dervishes. If we want to be men, we must carry out the dictates of civilization. We draw our strength from civilization, scholarship and science and are guided by them. We do not accept anything else."

In

a span of less than ten years he had resurrected a people with “Loser”

stamped upon their foreheads into a force to be reckoned with, deserving

of respect. He had the populace in his pocket and was nearly

universally beloved by his people and respected by his enemies. To this

day it is against the law to insult his memory or destroy anything that

represents him. There is even a government website that polices and

denounces those who violate this law, which has been in force since

1951.

In

a span of less than ten years he had resurrected a people with “Loser”

stamped upon their foreheads into a force to be reckoned with, deserving

of respect. He had the populace in his pocket and was nearly

universally beloved by his people and respected by his enemies. To this

day it is against the law to insult his memory or destroy anything that

represents him. There is even a government website that polices and

denounces those who violate this law, which has been in force since

1951.

“Women, for Mustafa, were a means of satisfying masculine appetites, little more; nor, in his zest for experience, would he be inhibited from passing adventures with young boys, if the opportunity offered and the mood, in this bisexual fin-de-siècle Ottoman age, came upon him.” (Patrick Balfour, Lord Kinross)

In short, this man engaged in occasional sexual dalliances with young men, yet he was briefly married to a woman.* In the two biographies I have read, Atatürk comes across as an omnisexual, using sexual prowess as just another tool of intimidation, a man obsessed by conquest. If he had been a guest in my home, I’d have feared for my larger houseplants. His libidinous influence is felt today – Turkey is the only Muslim country where homosexuality is not against the law.

*He had seven adopted children: six daughters and one son. Ulku Adatepe, just nine months old when adopted by Atatürk, died a few summers ago in an automobile accident at age 79. As a young girl she had traveled with her adoptive father as he traversed the entirety of Turkey to teach the new alphabet to his people. She was just six years old when Atatürk died.

All that off towards one side, Atatürk’s veneration has been constant since his death in 1938, nearly 75 years ago. His photograph appears on the walls of restaurants, shops, schools and government offices. His image is on banknotes, and nearly every Turkish town sports a statue or bust of the man. Your blogger knows this first-hand, since I have just returned from my second trip to Turkey this calendar year. At the exact time of his death, on every November 10, at 9:05 a.m., most vehicles and people in the country's streets stop for a minute of remembrance.

"A man born out of due season, an anachronism, a throwback to the Tartars of the steppes, a fierce elemental force of a man. With his military genius and ruthless determination, in a different age he might well have been a Genghis Khan, conquering empires."

Never in doubt of his abilities, the man excelled at every task he took on. Time and again he developed battle plans that succeeded against impossible odds. His triumph at Gallipoli against the British and Australians was nothing short of a miracle. As well, his powers of persuasion were legendary. I quote a speech he made to foreigners whose family members or loved ones had lost their lives and lay buried on Turkish soil:

"Those heroes (who) shed their blood and lost their lives... you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us – where they lie side by side here in this country of ours... You, the mothers who sent (your) sons from far away countries, wipe away your tears. Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well."

Amazing, no? The Turkish War of Independence, which ended in 1922, was the last time Atatürk used his military might in dealing with other countries. Ensuing foreign issues were resolved by peaceful methods during his presidency.

During his days as a Military Attaché in Sofia, Bulgaria (1914-1915), he adopted western European dress for the first time, usually wearing a business suit with a vest, since he had been ridiculed for his fez and Turkish military attire. He was astonished that neighboring Sofia, so near to Turkey’s doorstep, boasted an opera house, theatre, national library and a ballet company. He determined then and there that Turkey’s future must be forged upon Western European models, and that it must shed its backward, Islamic traditions. A staunch agnostic, Macedonian-born Atatürk turned the Islamic Turkish nation upside down. After seizing control of the country he abolished centuries of Shari’ah (Islamic) law, eliminated the Caliphate, implemented the Western European calendar, sent the Sultan into permanent exile and ordered Islamic religious schools closed. He cracked down harshly on once-powerful religious orders, such as the dervishes.

But he was just getting warmed up. He opposed the Turkish government's decision to surrender to the Allies after WW I, so he organized an army of resistance, which successfully defeated the Allied occupation forces. Atatürk changed the name of Constantinople to Istanbul and established a Republic with a new capital in Ankara, a more centrally located city. Atatürk became the Republic's first president. He once more set his sights on reform by banning the veil and fez, leading by example; he strutted around in Panama hats and western business suits before a shocked public. He gave women the right to vote, thus making Turkey the first Muslim country to do so. He ordered men to appear in public with their wives – even to dance with them; prior to this decree most Turkish men had never before met each other's wives. In his spare time Kemal banned polygamy. Oh, I nearly forgot – he forced everyone to take a surname. His own surname, Atatürk (meaning "Father of the Turks"), was granted to him, and forbidden to any other person, in 1934 by the Turkish parliament. He abolished the use of Arabic script and replaced it with a Latin (West European) alphabet, at the same time making secular public education compulsory, even for women, thus thumbing his nose at centuries of Islamic segregation of the sexes.

"Fellow countrymen," he declared, "you must realize that the Turkish Republic cannot be a country of sheikhs or dervishes. If we want to be men, we must carry out the dictates of civilization. We draw our strength from civilization, scholarship and science and are guided by them. We do not accept anything else."

In

a span of less than ten years he had resurrected a people with “Loser”

stamped upon their foreheads into a force to be reckoned with, deserving

of respect. He had the populace in his pocket and was nearly

universally beloved by his people and respected by his enemies. To this

day it is against the law to insult his memory or destroy anything that

represents him. There is even a government website that polices and

denounces those who violate this law, which has been in force since

1951.

In

a span of less than ten years he had resurrected a people with “Loser”

stamped upon their foreheads into a force to be reckoned with, deserving

of respect. He had the populace in his pocket and was nearly

universally beloved by his people and respected by his enemies. To this

day it is against the law to insult his memory or destroy anything that

represents him. There is even a government website that polices and

denounces those who violate this law, which has been in force since

1951.

In 2007 the Turkish government blocked YouTube throughout

the country for 30 months, in retaliation for four unflattering videos

about Atatürk that alleged that he was a Freemason and a homosexual,

citing a book printed in Belgium that is still banned in Turkey –

international standards of free speech be damned. I don’t know about

Freemasonry, but my research has shown that Atatürk was not a

homosexual. He was bisexual and always preferred the company of

men. I will quote a passage from this book – one of the most awkward and

tortured examples of syntax I’ve ever read:

“Women, for Mustafa, were a means of satisfying masculine appetites, little more; nor, in his zest for experience, would he be inhibited from passing adventures with young boys, if the opportunity offered and the mood, in this bisexual fin-de-siècle Ottoman age, came upon him.” (Patrick Balfour, Lord Kinross)

In short, this man engaged in occasional sexual dalliances with young men, yet he was briefly married to a woman.* In the two biographies I have read, Atatürk comes across as an omnisexual, using sexual prowess as just another tool of intimidation, a man obsessed by conquest. If he had been a guest in my home, I’d have feared for my larger houseplants. His libidinous influence is felt today – Turkey is the only Muslim country where homosexuality is not against the law.

*He had seven adopted children: six daughters and one son. Ulku Adatepe, just nine months old when adopted by Atatürk, died a few summers ago in an automobile accident at age 79. As a young girl she had traveled with her adoptive father as he traversed the entirety of Turkey to teach the new alphabet to his people. She was just six years old when Atatürk died.

All that off towards one side, Atatürk’s veneration has been constant since his death in 1938, nearly 75 years ago. His photograph appears on the walls of restaurants, shops, schools and government offices. His image is on banknotes, and nearly every Turkish town sports a statue or bust of the man. Your blogger knows this first-hand, since I have just returned from my second trip to Turkey this calendar year. At the exact time of his death, on every November 10, at 9:05 a.m., most vehicles and people in the country's streets stop for a minute of remembrance.